Back to the Feature: Breaking down the college exploits of a Kansas icon, Wilt Chamberlain (Part I)

Back to the Feature: At Kansas, Wilt was a fearsome defender, too

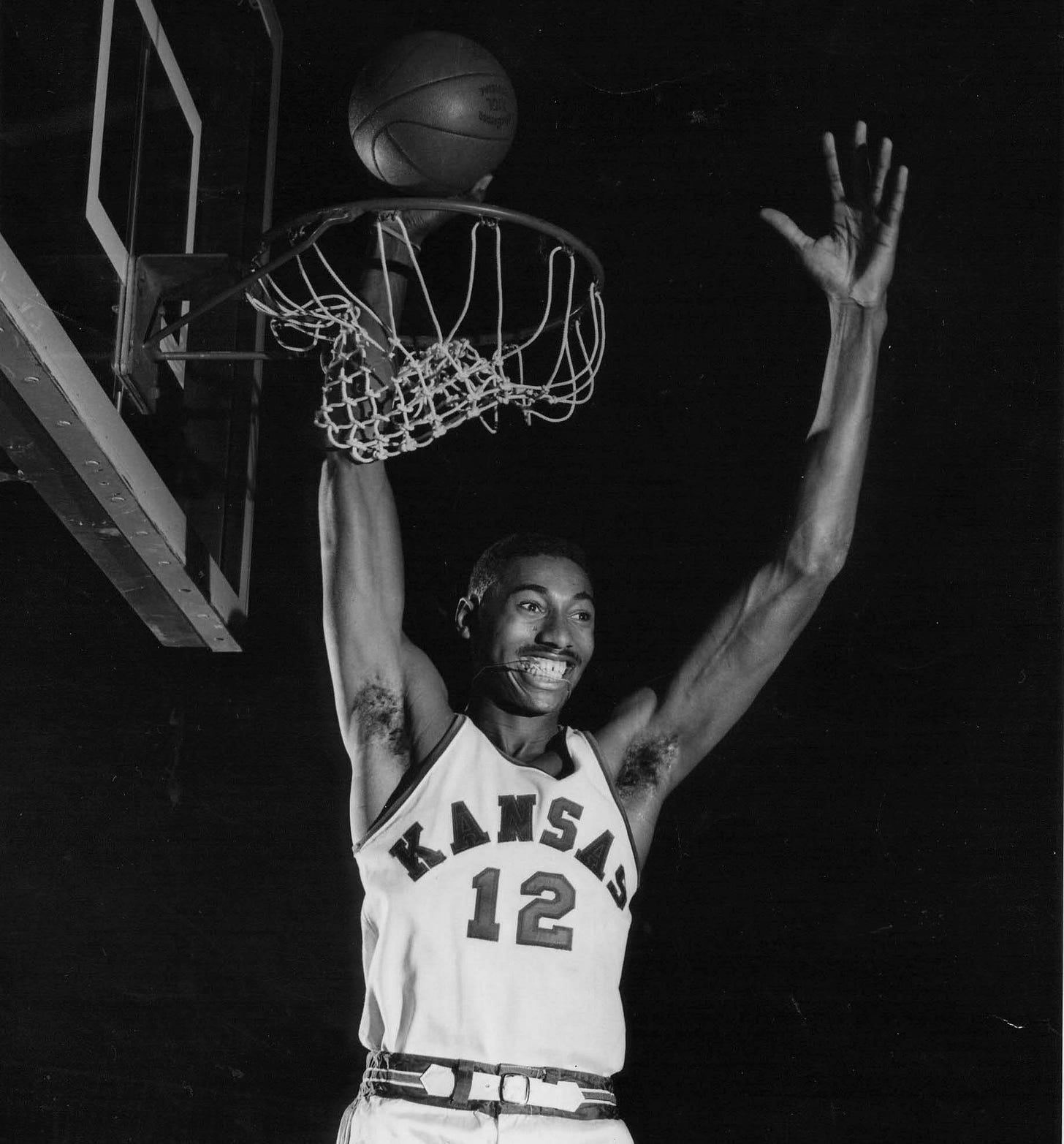

Wilt Chamberlain (Kansas Athletics)

By Joseph Dycus (@joseph_dycus)

Wilt Chamberlain is the most notable scorer in professional basketball’s storied history. Even fans with only a passing interest in the game’s past have seen the famous picture of the 7-foot-1 Chamberlain, then playing for the NBA’s Philadelphia Warriors, holding a sheet of paper with “100” scribbled onto it after he hit triple-digits against the New York Knicks in 1962. More serious students of basketball history have no doubt heard the famous refrain “excluding Wilt Chamberlain” when discussing scoring statistics or seen the incredible list of point-related records under Chamberlain’s name in the NBA record book.

But what about the other end of the court? Well, would you believe me if I told you a 20-year-old Chamberlain was even better at stopping shots than he was at making them?

Such an assertion sounds preposterous but give me a chance to change your mind. Chamberlain’s collegiate career at Kansas is almost a footnote in any biography, a brief three-year pitstop before he authored a large chunk of the NBA’s statistical point-centric record book. And make no mistake about it, Chamberlain’s scoring numbers were almost as gaudy as one could expect in a game without a shot clock—an average of 29.9 points in 48 games across two seasons (1956-57 and ‘57-58) as the focal point of every defense is admirable (and the subject of a future article in this space), without a doubt.

“He easily has greater possibilities than any player we ever had here," legendary Kansas coach Phog Allen told The Sporting News in 1955. "He has coordination, can run, and can jump. He can do everything. A fan simply can't realize the effect of such an overpowering man. He just paralyzes smaller players.”

But buried underneath this avalanche of statistics and numbers is another pile of digit-based evidence for Chamberlain’s dominance as a Jayhawk, accessible only through film study and careful tracking. Now there is one disclaimer: of the six Kansas games available on YouTube, only four—against SMU, Oklahoma State, San Francisco, and Colorado—are complete from start to finish. The famed 1957 NCAA tournament title game against North Carolina, and an upload from Northwestern, both jump back and forth between different points, making it difficult to figure out what is repeated footage and what isn’t. So, these statistics come from four complete games and a couple of partial tapes.

With that disclaimer out of the way, there was still much to be gleaned from these glimpses into how unstoppable a young Chamberlain was on defense. In the available footage, he contested 81 shots, with 43 of those being at the rim. This should come as no surprise because asking the tallest player on the court to be the last line of defense is common sense.

You know what isn’t common sense? A 21 percent accuracy rate on those shots three feet or closer from the rim. While defensive statistics on the collegiate level are hard to find, NBA statistics show that Rudy Gobert, the best interior defender in the world’s best league, holds teams to 48 percent shooting around the rim. While the quality of the players attempting those shots is considerably higher than the 1950s collegians trying to heave shots over Wilt, that is still an astounding statistic.

One of the most basic ways to judge rim protection is by looking at how many shots a player blocked, and Chamberlain blocked plenty of shots as a Jayhawk. Mind you, most of these game clips came from the NCAA tournament and conference play, not against overmatched D-II scrubs from the middle of nowhere. So, try to imagine any modern-day player blocking 38 shots and conceding only 19 in shots where he was the primary defender.

Yes, you read that correctly—a 2:1 block to made shot ratio, and a little under half of all shots contested ending in a block (47%). Oral Roberts’ Max Abmas became a household name by becoming America’s most beloved 3-point gunner on 2021’s Cinderella school. Chamberlain’s contest to block rate was actually higher than Abmas’ shot to make rate. His defense was so absurd he holds his own against shooting splits by the game’s best marksmen.

To combat this, some teams tried to draw Chamberlain out to the perimeter, in theory creating driving lanes for their smaller players while trying to get their center easier baskets of the catch-and-shoot variety. This approach had some mixed results in the six games watched. SMU had future NBA center Jim Krebs operate as a proto-Channing Frye in its tournament game against the Jayhawks. The result was an 8-28 shooting night while being ineffectual from distance. There is a real argument that Krebs was the best competition Chamberlain would play that season, and that’s how he treated his most talented “rival.”

Chamberlain even blocked a couple of Krebs’ jumpers, which was commonplace in the tape that is available for public consumption. While part of this had to do with playing on a condensed pre-3-point line court where “outside shooting” pertained to anything chucked up more than 12 feet from the basket and great rim-protectors were allowed to park in the lane indefinitely, it was also a testament to Chamberlain’s insane reach and springiness. When teams dared to test him outside, they shot 10 of 38 from the floor and sometimes saw their shot snatched out of midair.

“He blocked a few Colorado shots,” Bob Busby casually wrote in the March 10 edition of the Kansas City Star after Chamberlain swatted away 11 against Colorado.

On a related note, if there is one minor nitpick you could have of Chamberlain’s defense, it’s his penchant for getting away with apparent goaltends that would probably be called in today’s game. Of course, can one blame the refs for not awarding two points to the victimized side? It’s doubtful they had ever seen anything like Chamberlain before.

The other criticism someone could reasonably place at Chamberlain’s feet is that he would occasionally have inexplicable lapses in concentration, where a driver would take the ball into his airspace and Chamberlain would just … stand there. He could have swatted the ball into the stands if he had just moved his arms, but it almost seemed like Chamberlain had a brain freeze. Here’s a play against San Francisco where Chamberlain could have forced a miss but didn’t for whatever reason.

This critique is almost pointless though because Chamberlain was an active and engaged defender for the other 99 percent of the game. His defense was often the best of both hypothetical worlds—flashy and effective. And sometimes he didn’t even have to play defense to have an effect. His mere presence on the floor deterred shots from inside 12 feet and encouraged long bombs from modern-day 3-point range. Shot-making from these distances is a large reason North Carolina had such success against Chamberlain’s Jayhawks in the 1957 NCAA championship game.

Aside from holding the ball (like many teams did to prevent Chamberlain from touching it), Frank McGuire’s boys spread the Jayhawks out and forced Chamberlain to defend in space. Such a play created this layup early in the game, where the Tar Heels brought him up to above the elbow in order to get him out of position on the ensuing cut.

While Kansas eventually fell in triple-overtime to North Carolina, his defense wasn’t what was questioned. Giving up 54 points in three overtimes is nothing to be ashamed of. No, it was the more “glamorous” aspect of Chamberlain’s game that came under fire. In the next edition of Back to the Feature, we will take a look at the much more publicized part of Chamberlain’s legacy—his scoring prowess. Some of what we learned in our research will surprise you.

Thanks for reading!

If you like what you’ve read since we started this newsletter last August, tell your friends about us.

If you want to receive more stories like this one, subscribe to our paid tier for only $7.99 per month (or save $24 per year with an annual subscription).

Also, be sure to snag the historic 40th-anniversary edition of the Blue Ribbon College Basketball Yearbook before this collectible item is gone.