Back to the Feature: Breaking down the college exploits of a Kansas icon, Wilt Chamberlain (Part 2)

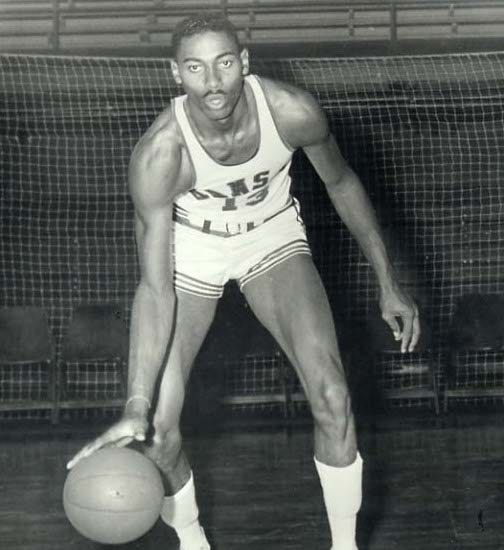

Wilt Chamberlain (Kansas Athletics)

By Joseph Dycus (@joseph_dycus)

“I think most fans and sportswriters subconsciously resented my ability to do so many things so well; I could shoot, rebound, pass, run, and blocks shots. That made me seem almost inhuman.”

Wilt Chamberlain in 1973

Is there a more hated player in team sports than the big man? Go to any pickup game in America and listen to the way his teammates grumble about the giant who tries to play like the guards on the posters adorning his childhood bedroom. ‘Stop shooting! You’re bigger than everyone else! Play inside!’ their teammates mutter.

And yet inversely, if that same player pounds the boards and swats away every shot while converting every lightly contested layup he takes over lilliputian adversaries, those watching will still be unsatisfied. “Of course he’s kicking ass. He’s taller than everyone else, so he doesn’t need any skill! If I could touch the rim without jumping, I’d be so much better than that scrub!” No matter what he does, the gifted skyscraper will be invalidated by those who stand smaller and/or less talented.

Such was the life of Kansas star Wilt Chamberlain, who was damned by the masses off the court while dominating them on it. In the 50 years since his retirement and quarter-century since his death, the mythology surrounding the 7-foot-1 phenom from Philadelphia has seen a book of tall tales spring up around the man’s physical gifts. Chamberlain could grab 50 rebounds in a game, score 60 in a quarter, block ten shots in overtime, and then sleep with as many supermodels after the final buzzer. He could pick up a car with one hand while swimming across the Hudson River in the middle of January. His leaping ability rivaled an Olympian’s and his 40-yard dash time was said to be faster than Jim Brown’s when measured by Hall of Fame NFL coach Hank Stram one offseason.

“Wilt asked me if I wanted him to start catching the ball. I threw again and he leaped up, flat-footed, and caught it. I kept throwing. After a bit he was catching the ball with one hand like he was wearing a baseball glove,” Stram wrote in his 1986 memoir They’re Playing My Game. “How could you possibly defense him? You’d have to have a 7-foot defensive back… I was all ready to sign him for the Kansas City Chiefs, but his basketball club had other plans for him.”

Wilt Chamberlain’s fantastical tales are mostly a product of his incredible NBA career, where he still holds just about every scoring record and a good number of rebounding records, too. If the NBA had kept block and steal numbers, he doubtlessly would have held most of those records. He once averaged 50 points in a season, and then followed that up by scoring 44 points a game. Chamberlain’s scoring exploits at Kansas are less remembered but still extraordinary when placed into context. He averaged 29.9 points per game in an era without a shot-clock but filled with teams happy to give up open 12-foot jumpers to his teammates if it meant Chamberlain didn’t touch the ball. If this didn’t work, those teams held the ball like a petulant child who hasn’t learned the virtue of sharing.

“No one guy is going to take over any sport—not me or Joe Namath or Willie Mays or anyone,” Chamberlain said in his 1973 autobiography Wilt: Just Like Any Other 7-Foot Black Millionaire Who Lives Next Door. “But the way the coaches and athletic directors and rule-makers acted, you would’ve thought I was a monster from the deep, out to destroy their game, rape their wives, and eat their children alive.”

And yet... when placed in further context, Wilt Chamberlain’s scoring numbers begin to appear downright pedestrian. How in James Naismith’s world does the most incredible athlete to ever grace the hardwood shoot 47 percent from the floor even though he towers over every opponent? Six and a half decades after Chamberlain’s stay in Lawrence, modern-day Jayhawk big man Udoka Azubuike somehow shot a preposterous 75 percent from the floor despite having few offensive skills and even fewer athletic gifts compared to Chamberlain and his arsenal of fades, spins, finger rolls, turnarounds, and fakes.

But that last sentence is the entire reason Chamberlain’s scoring effectiveness was nowhere near as gaudy as a rational person would expect it to be. See, the man dubbed “The Big Dipper” by journalists awed by his ability to effortlessly dunk basketballs in a crowded paint loathed this nickname and the connotations that came with it. Like dozens of big men who worked and trained to be the best they could at their craft, Chamberlain bristled at suggestions he was merely a brute who slew teams with superhuman size and athleticism. And yet the conditions under which he toiled at Kansas did their best to hide those slick moves he longed to display. How could he spin and pirouette and juke his way to two points when he was operating in a space where two defenders were glued to his back and a third was fouling him from the side?

“Other teams would double-and triple-team me, and I’d have to run up and down the court carrying half the other team on my back,” Chamberlain said in Millionaire. “It was more like an earthquake evacuation than a basketball game, except the guys I was carrying were trying to knock me down and beat me up.”

“They came out with zone defenses and stall tactics. If we had a shot clock, it would have been a different ballgame,” Kansas teammate Maurice King told the Lawrence Journal-World in 2007. “I think he got tired of all that and the zone defenses and figured he might just as well take his game to somewhere he can get paid.”

And yet tucked away in the recesses of YouTube’s 17-year archive are entire videos and portions of six of his Jayhawk games, and they give a fascinating glimpse into Chamberlain’s paradox. He longed to be freed from the restrictions shackled on him by college defenses, to show the world his many scoring talents. And yet, by watching those games, even though those talents glimmer through like a diamond in the dirt, one comes to the conclusion the best way for basketball’s Goliath to play was in the prison-like setup he had in Lawrence.

Chamberlain shot more than 52 percent in the clips we have (59-113 from the field), and sample size is an issue. But with that said, his complete domination, whenever he catches the ball inside of five or so feet from the rim, is unfathomable. Despite being surrounded by limbs and fouling hands, he would mechanically and brutally find a way to power through contact for layups and dunks. Chamberlain was decisive in these moments, usually taking a single dribble, or often forgoing that step and just using his lithe frame and a nimble pivot foot to find space before scoring two points.

“The Stilt is most effective simply because of his physical qualities,” Don Pierce of TheSporting News wrote in 1955 after watching Chamberlain dominate the Kansas varsity as the star of the freshman team. “He stands 7-feet in his sweat socks. Over this frame are spread 225 sinewy pounds. He is almost as agile as a 5-11 playmaker. He can jump 24 inches straight up.”

“Against the varsity, he was not bothered noticeably by the new 12-foot lane,” Pierce continued, making a comparison that would come to define Chamberlain for the next 70 years. “His timing on the slightly off-target shots of his mates, in another year, will match that of Bill Russell, the fabulous human funnel of San Francisco. Spectators can actually see his pie-plate hands jam down inside the net.”

Wilt Chamberlain was not looking to pass in these situations, but it would be unfair to label him a ball hog. Sixty-nine of his shots would be considered assisted by most scorekeepers today, as Chamberlain rarely dallied with the ball in his hands. Even a good number of his unassisted shots were of the put-back variety, and not a product of him isolating or pounding the ball into dust. Everything he did was quick and with a purpose, as opposed to his mannerisms a decade later with the Los Angeles Lakers, when Chamberlain was famous for holding the ball and waving it to and fro as he waited for teammates to cut around him in a planetary manner.

And while Chamberlain was not a passer by any means, asking him to pass in these situations would have been malpractice by Dick Harp and Kansas’ coaching staff. Why would someone ask Chamberlain to give up a surefire scoring opportunity three feet from the rim just so one of his less-talented teammates could fire up a brick from 13 feet away? Now of course, that clanger off the rim would be wide open because of the extreme lengths teams went to make sure Chamberlain didn’t get the ball in these advantageous zones.

So terrified were teams of the thought of an unmarked Chamberlain that they often crammed as many defenders as possible into the lane and were content to give up open shots from the elbow if it meant the giant was not scoring. And of course, there was also the fact the NCAA changed the rules to make sure Chamberlain did not break the game.

“They also put in the offensive goal-tending rule about the same time; you couldn’t touch the ball when it was on the rim or in the imaginary cone above the basket,” Chamberlain said in Millionaire. “That was to keep me from guiding my teammates’ shots in.”

And yet, there is a solid argument to be made that guarding Chamberlain with one man was often the way to go if that one defender could keep him far enough away from the basket. Remember how we mentioned Chamberlain’s desire to be seen as more than a dunking specialist? Well, this manifested itself in his famous fadeaway. The nonexistent spacing and perpetual double- and triple teams after the catch made dream-shaking impossible but meant the fallaway jumper was an option. Even when guarded by multiple defenders, Chamberlain could always elevate over their petty contests for an unblockable shot.

“He was always someone who wanted to be recognized not just as a player who stood around the basket, but as a man of great talent” University of Memphis professor Aram Goudsouzian, author of Can Basketball Survive Wilt Chamberlain? says. “He always wanted to showcase his individual greatness but had to do so within the context of a team sport.”

It was a great bailout shot, as shown at the end of Kansas’ first-round showdown with SMU, where Chamberlain broke the Mustangs’ overtime stranglehold with a fadeaway over three defenders. The issue was that Chamberlain didn’t just use it as a last resort—it was sometimes his first option when he caught the ball. In a 1957 matchup with Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State), the Cowboys defended Chamberlain with only one defender. Rather than smash and pound his way into deep paint touches, Chamberlain instead settled for 11 turnaround jump shots, which made up almost half of his 23 shots recorded on film. Chamberlain connected on only four, a troubling statistic proven by later games to be part of a trend rather than a poor performance.

“When I did shoot regularly from the outside, in high school and college, I could really hit,” Chamberlain said in Millionaire in a quote that indicated his misguided trust in his shot lingered far into his pro career. “In fact, my high school coach always said my jump shot from the foul line was my best shot; some of the national sportswriters who came to Philadelphia to see me play back then said the same thing.”

In the partial tape that exists of a game against Northwestern later that year, Chamberlain went to the fadeaway on 15 of his 21 attempts and made only seven (although it should be noted Chamberlain shot only 1 of 6 on non-fadeaways). Northwestern’s coach Bill Rohr had Wilt’s future Philadelphia Warriors backup Joe Ruklick stranded on an island against the behemoth. Big Joe must have enjoyed reading Robinson Crusoe as a child because he did more than just survive against Chamberlain. Ruklick was successful in pushing Chamberlain away from the rim, and rather than fighting to get closer, Chamberlain used it as an opportunity to show off his shooting touch.

“I still insist we're much better off to play this Chamberlain straightaway, man-for-man, concede him 30 points but make him work for them,” Kansas State coach and triangle offense wizard Tex Winter told Sports Illustrated in an article published on February 10, 1958. “Don't give him the easy ones, try to box him out under the boards.”

Or perhaps the more apt phrase is “lack of shooting touch,” because Chamberlain hit on only 17 of 49 turnarounds or a paltry 35 percent of those outside shots. In a vacuum, that is not a terrible percentage, because fadeaways tend to be more difficult shots and are usually converted at a lower rate by even the best shooters. The issue is that Chamberlain shot 42 of 64 (66 percent) on non-fadeaway jump shots tracked over the six games on YouTube. And these numbers are bogged down by his habit of also trying pullup and twisting jump shots on occasion.

And so, without context, his decision to take almost half of his shots in a manner that resulted in him making only a third of them, when an automatic bucket (or at least free throws) was available to him is a frustrating one to watch repeatedly happen in every game. As mentioned earlier, while triple-teaming Chamberlain seemed to be the way to go when stopping him from raining fire upon defenses, the opposite ended up being true. In a game against Colorado, Chamberlain made 13 of 18 shots, and only five of those shots were of the turnaround variety.

The Buffalos triple-teamed Chamberlain at all times, and so most of his attempts came on either lobs, put-backs, or other duck-ins where he caught the ball and finished like a modern-day rim-runner. And while Chamberlain had precious few opportunities to run in transition thanks to sticky-fingered opponents who would rather pound and squeeze the air out of the basketball than allow him a chance to score in the open court, he did occasionally flash the great speed NFL legend Hank Stram spoke of so glowingly of in his book.

The last aspect of Chamberlain’s less-than-ideal shot selection we have yet to discuss is an unavoidable topic in the 1950s in which Chamberlain grew up. With the exception of Bill Russell and possibly George Mikan, there was no prior archetype for Chamberlain to follow as a physically dominant big man. And as a Black man who famously “integrated” Lawrence Kansas, he had to navigate the overt racism and beliefs that opposed the Black citizens of a segregated America. A common stereotype was that the Black athlete was naturally unskilled and unintelligent, and relied solely on physical prowess to play his sport well.

“They helped create a climate in which it was easy for many fans to dismiss my accomplishments as an accident of height and race,” Chamberlain said of sportswriters in Millionaire. ”’He’s so big; he should be great’ or ‘All those n*****s are good at sports; they can’t earn an honest living at anything else.’ ”

Chamberlain’s inability to live up to expectations higher than Everest did not help his cause either. Chamberlain’s first season in Kansas came up just short of a championship, Kansas losing to Frank McGuire’s North Carolina team in triple overtime in 1957’s title game. Against a Tar Heels squad comfortable holding the ball as part of a methodical attack, Chamberlain contributed 23 points and 14 boards in a one-point loss. Good numbers, but a step below the 29 and 18 he averaged during the year.

“What develops as the criticism of Chamberlain is that it’s not the individual stuff, it’s that he can’t lift his team to greatness even though he does win two titles in the NBA,” Goudsouzian says. “I would say the narrative gets set at Kansas, especially after the sophomore season. Although you could say they went 26-2 and went to the NCAA final and lost in triple overtime, so it’s not like he was abandoning his team. He was obviously one of the greatest players in basketball history. But that narrative that gets set, it dogs him for sure.”

Because Chamberlain was (and in many ways still is) the most prominent example of a player who utilized immense physical gifts to control the game of basketball, he was easily cast as the manifestation of every racial and athletic stereotype from the era. And so who can one blame Chamberlain for wanting to “play like a guard” and show the world he was more than just a tall man who could jump? The cruel irony is that in the years to follow, it was actually big men who played a perimeter-oriented offensive game who were deemed “soft” and undesirable. Posting up the center and letting him pound away from the low block was eventually deemed the preferred method of attack for coaches and remained that way until the 3-point revolution in the 90s.

It was into this environment that the closest analog we have to Chamberlain emerged in Shaquille O’Neal. By this point, big men were chastised if they left the painted area, and so O’Neal never bothered with developing a jump shot or any semblance of a perimeter game. Everything was in the post or around the rim, a bludgeoning attack against double- and triple teams. It was effective in both the NCAA and NBA, and yet Shaquille O’Neal was constantly hounded by questions about what he could or did not do outside of this highly efficient zone.

“Just the idea of a 7-foot-1 guard would freak out most fans. But for me, it was a good basketball decision,” Chamberlain said in Millionaire about his stint with the Globetrotters post-college, where he played on the perimeter for the world’s most famous team. “It gave me a chance to handle the ball and shoot from the outside and practice all those skills I’d need in the NBA but had been denied in college.”

And so, while Chamberlain may have been better served (and his teams benefited) from a more selective scoring repertoire, it’s very likely he would never have been able to escape criticism of his game. Hell, even bringing up some efficiency issues with a man who put up 30 a game in college while putting every frontcourt in foul trouble feels like nitpicking at best.

Such was Chamberlain’s curse—great, but those smaller and less talented than him always saw ways he could have been better.