Blue Ribbon Report, Vol. 19: Hofstra’s Cramer doesn’t miss a beat after three-year layoff, Back to the Feature series

Today’s edition of the Blue Ribbon Report

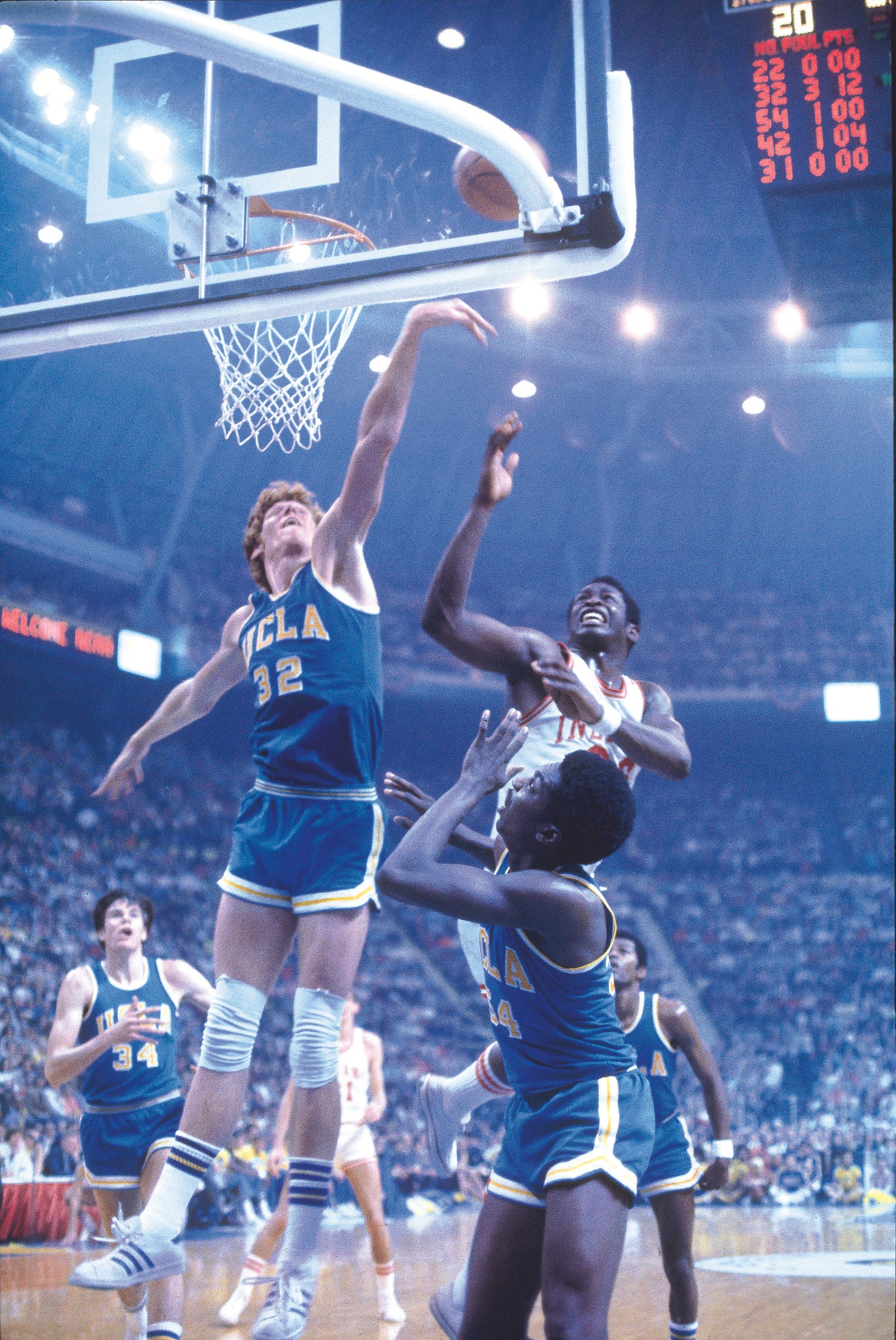

Joseph Dycus looks at a classic performance from Bill Walton during his career at UCLA

Patrick Stevens shares the story of Kvonn Cramer’s return at Hofstra

Back to the Feature: Blue Ribbon Salutes Great Moments in College Hoops History

Bill Walton (UCLA Athletics)

By Joseph Dycus (@joseph_dycus)

If you are under the age of 40, you probably know Bill Walton as the zany color-commentating character who fills the airwaves with a steady stream of verbose soliloquies next to his mildly annoyed play-by-play partner Dave Pasch on ESPN broadcasts. And that's a damn shame, because once upon a time, William Theodore Walton III was the finest player in collegiate basketball for three consecutive seasons.

Counting his time on the freshman team at UCLA, Walton's Bruins won 93 consecutive games. Few games are more famous than his 80th straight win, in which he made 21 out of 22 shots against a Memphis State frontcourt featuring future all-star Larry Kenon and pushed UCLA to its seventh national championship in as many seasons.

But Walton's brilliance was on display in every game he played, from nationally televised March Madness spectacles, to mid-winter West Coast contests accessible only to viewers with a ticket or astute listeners with a half-decent radio. Aside from archived newspaper accounts and vague box scores placed in the deep recesses of Basketball Reference, there is no way of comprehending the kind of basketball artistry displayed during these 40-minute performances.

And so, whenever a new bit of footage is unearthed, it is cause for celebration.

In 2015, Washington State University Libraries' Films uploaded a brief portion of UCLA's 55-45 win over the Cougars in January 1974. The silent coaches’ film is only 12 minutes and 11 seconds, but it contains more than enough evidence of Walton's brilliance and skillset. In just under a quarter of an hour, the big redhead displayed his scoring touch, uncanny mobility, rare dexterity, and the facilitating genius collegiate basketball has not since seen since his graduation that summer. So daunting was the premise of slowing Walton, even Washington State coach George Raveling perceived the chances of a Cougar victory to be dismal at best.

"We've got to play to near perfection... and UCLA is gonna have to play a poor game, one of its poorest games ever," Raveling told the Los Angeles Times before the game.

Early, Washington State appeared to be playing a man-to-man defense with its guards, while the three frontcourt players were arranged in some kind of zone along the baseline. On one possession, Walton established position on the left block against an undersized forward and then pivoted to his right. As he began to loft the ball upward over his left shoulder, freshman center Steve Puidokas shifted to the middle and contested the shot. Puidokas was no scrub—he averaged 17 points that year and still ranks second all-time at Wazzu in career points and rebounds. But he was no Bill Walton, either, and he had no chance at stopping Walton's Kareem-esque (or is it Alcindor-esque?) skyhook. It was a fitting shot and a noble tribute to the demigod of a pivot Walton had replaced in Westwood.

"Alcindor was arguably the greatest high school player who ever lived and was well known to everybody who followed basketball with any kind of intensity," says legendary Boston Globe columnist Bob Ryan. "Bill Walton was known in California, but the name people knew was Tom McMillen in Maryland. Walton was not a national phenomenon coming out of his freshman year like Lew Alcindor was."

Back to the game. A few moments later, Walton tracked one of the Cougar forwards along the baseline, took away the scoop layup, and then smacked the ensuing turnaround jumper into the corner like a ping-pong ball meeting its paddle. But unlike many modern-day shot-blockers, Walton had the good sense to keep the ball in play, which allowed one of UCLA's guards to track the ball down and start a fast break. Even though Walton's passing was his trademark, his defensive ability was a close second. Before his feet betrayed him and sapped the ginger giant of his athleticism, the man was the definition of an explosive athlete, able to spring above his competition like a geyser at Yosemite.

"As for his defense, I think that’s the most underrated part of his game," says UCLA basketball historian Spencer Stueve. "He was a tremendous back line defender. He protected the rim, was a great rebounder, and a great outlet passer. He would challenge shots, block them or force a miss, grab a rebound, fire an outlet to mid court and ignite the fast break."

But Walton was far from just a run-and-jump athlete, as the paying customers at Friel Court soon discovered. One of Washington State's guards broke through UCLA's vaunted press along the right sideline and began to cut back to the middle. Bruin swingman and future NBA all-star Keith (Jamaal) Wilkes recovered quickly enough to take away the pass to the trailing Cougar, but there was still another WSU player cutting in from the right corner as the guard made his way into the paint. Walton was the only player who had a chance at preventing a score, and it would have been unfair to ask a single player to shut down a textbook two-on-one break.

But for a player Walton's caliber, such a request was perfectly reasonable. Instead of committing to the ball handler, he stayed in between the ball, the basket, and the cutter. When the ball handler made his pass, Walton jumped straight up and flung his hands to the sky. This frazzled the passer, and the ball was thrown at 100 miles per hour behind his teammate, prompting an enthusiastic dance from the referee as he signaled a change of possession.

Walton's last notable play came ten minutes into the video, when he began the possession on the right block. Even though he was single covered, Walton was not thinking of scoring. Instead, he was scanning the floor in search of an open teammate. For all of his athleticism, scoring moves and defense, Walton's true trademark is his peerless ability to spray passes to every nook and cranny of the court. From dimes over the shoulder to cutters, to full-court bombs after a defensive rebound, there was no pass Walton could not or did not make.

"I have long maintained he is the greatest passing big man, and the only challenger before Nikola Jokić came along was Johnny "Red" Kerr, who was more noted for his passing than any other center," Ryan says. "Then Walton matched him in the half-court, and made outlet passes Kerr could never dream of making."

On this particular possession, he made a basic but useful toss to the top of the key, where his teammate had an opportunity to take an open 17-footer. But instead of glorifying himself, the Bruin guard made the selfless play and swung the ball to the baseline for a better shot. This picturesque example of Bruin basketball under John Wooden had something of an anticlimactic end though, with the shooter missing his attempt. But this outcome simply served as an opportunity for Walton to showcase his supernatural ability to control the boards, and Walton easily tipped the ball over Puidokas and into the basket for an easy two points.

"The most under-appreciated aspect of his game was his rebounding, and I'm talking about his technique," Ryan says, highlighting in particular his defensive rebounding acumen. "Picture this now: he would pick the rebound coming off the rim at the instantaneous moment, when you couldn't say if it was goaltending or not because it was timed so well. Picture him getting the rebound in his right hand and scooping the ball into his left like you are scraping crumbs off a table. We've all done it and do it. You sweep the crumbs off the table. That's how he swept the ball off the basket for a rebound."

The rest of the game is still hidden away somewhere in a Washington State vault, but box scores and newspaper clippings tell us Raveling's team did not play to near perfection. The result was a ho-hum and predictable 55-45 UCLA victory over yet another overmatched Pac-8 opponent and another inevitable continuation of its march toward another undefeated season.

But history books also tell us 1974 was the end of UCLA's title streak. In a result only considered devastating for a program fresh off seven consecutive national titles, the Bruins bowed out of the NCAA tournament in the Final Four, victims of David Thompson's aerial warfare in a classic three-overtime game. While doubtlessly shocking the public at the time, the signs of descent were already present. First was a last-second regular-season upset against Austin Carr's Fighting Irish in South Bend. Then came two back-to-back close losses to Oregon and Oregon State mid-season, displaying a team far weaker than Alcindor's or even Walton's earlier outfits, even if many still thought of UCLA as an unbeatable juggernaut.

"It was inconceivable that they wouldn’t win it all again. What caused them to fall short was really just a failing late in games," Stueve says. "The metrics are actually pretty similar to the ‘73 team, not as good as ‘72, the second-best team in college basketball history in my opinion. There was plenty of talk after the season about Walton and Wilkes losing focus and motivation, but neither of them ever admitted to that as far as I’m aware."

But none of that was of any concern on a drizzly mid-1970s winter night in Pullman, and what followed afterward should not bother any of the 1,400 people who have bothered to watch the grainy, oversaturated, and noiseless film graciously posted five years ago.

All that matters is enjoying 12 minutes and 11 seconds of the best college basketball player of the last half-century.

GIFs courtesy of Washington State University’s Manuscripts, Archives & Special Collections.

Hofstra’s Cramer doesn’t miss a beat after three-year layoff

Kvonn Cramer (Hofstra Athletics)

By Patrick Stevens (@D1scourse)

At the first TV timeout of Hofstra’s season, freshman wing Kvonn Cramer checked in at the scorer’s table, which is usually the most mundane of tasks even in the oddest of seasons.

Not this time.

Cramer hadn’t played in a game since his sophomore year of high school. He spent three years on the sideline—two for reconstructive knee surgeries, a third while redshirting and getting readjusted to the game—and was finally entering his first college game.

He looked around the near-empty Rutgers Athletic Center and simply savored the opportunity to play basketball.

“The first game at Rutgers, it was just a moment I had to let sink in knowing I hadn’t played for three years,” Cramer says. “It was just a great moment for me knowing I’m back out on the court.”

Cramer has already claimed a Colonial Athletic Association rookie of the week award. The 6-foot-6, 205-pounder produced a double-double in his second career game, a 12-point, 10-rebound effort against Fairleigh Dickinson, and he’s averaging 8.5 points and 6.3 rebounds through four games for the Pride (2-2).

And this is just the beginning.

“You’re only starting to see it,” says Lisa Sullivan, his coach at Mount Pleasant High School in Wilmington, Delaware.

Mad hops and knee trouble

Sullivan distinctly remembers the first time she met Cramer. It was the summer before he was entering high school, and his mother brought him to a summer league game to see if he could get acclimated to the school and the program.

Cramer was nervous, and Sullivan assured him the point of the summer league was to improve rather than pile up a gaudy record. In addition to her coaching, she was also operating the clock, which meant occasional distractions.

At one point that day, her veteran point guard missed a pull-up jumper from the free-throw line, an otherwise forgettable moment except for what came next.

“Something came out of the ceiling and came down and crashed into the ball and threw it through the rim,” Sullivan says. It was Cramer. “We’re like ‘Holy hell. There’s no way this kid is in ninth grade and there’s no way we’re lucky enough to get him.’ I remember there were kids who were betting in Kvonn’s first six games if he would get a dunk. And I’m like ‘You should bet the first six seconds.’ ”

He was joining a program brimming with experience, and immediately made his mark. He averaged 12 points and six rebounds as a freshman, then 18 points, eight rebounds and four assists as a sophomore. Tickets for Mount Pleasant games, available only online, would sell out in minutes.

Cramer couldn’t have known when Mount Pleasant lost in the state quarterfinals on March 5, 2017 it would be another 1,366 days before he played in another game.

Mount Pleasant had high hopes as Cramer moved into the second half of his career. But in a fall league game about a month before his junior season began, he heard a pop in his left knee as he came down from a dunk.

The diagnosis: A torn anterior cruciate ligament. Surgery would cost him the entire season. Sullivan remembers how crushed Cramer felt, and how she and others consoled him with assurances he would still have a senior year.

Until he didn’t. About eight months into rehab, Cramer contracted strep throat. He felt lousy and ran a fever, leading to a trip to the hospital. There, he learned his knee was infected as well, and he had developed sepsis.

“It ate up 60 percent of the graft that was in my knee, so basically there was nothing there from the reconstruction of the ACL,” Cramer says.

Cramer had two options, neither of them good. He could play his senior year on a balky knee and risk a more severe injury, or undergo the same rehab process a second year in a row.

“He thought his basketball career was over,” says his mother, Gwendolyn Brown. “It was ‘Mom, I’m not going to be able to go to college.’ I said, ‘You’re going to go to college. Just relax. Everything is going to be fine. You’re going to play basketball again. But you can’t play on your leg.’ He wanted to try. … I kept saying ‘No, no, no,’ but you know how kids are. He wanted to ball.”

Mom won out. Cramer underwent another knee reconstruction rather than pushing it off.

“The second time around, I was sad, I was devastated. But the mindset was I already knew what I had to do to get to where I wanted to be,” Cramer says. “Just being a hard worker, I said ‘I’m going to get this done and come back even better than what I was.’ ”

Because part of both of his recoveries was spending plenty of time around his AAU and high school teams, Cramer, who picked up the sport late, expanded his knowledge of the game from the sideline. Even before the injury, he started to add perimeter-oriented elements to his game after playing primarily in the post in high school.

But it still hurt to be sidelined again.

“The last game his senior year that we lost and got knocked out of the playoffs he was just inconsolable in the locker room afterward, because I think he had all these hopes and dreams and he never got to realize them, unfortunately,” Sullivan says. “But I go back to the foundation that was laid [by his parents] when he was growing up, and that’s what got him through it.”

Hofstra finds a gem

How does the recruiting process for a guy who doesn’t play during the second half of his high school basketball career unfold? Cramer found out.

Even after missing his junior year, there was considerable interest. Rutgers, Seton Hall and VCU wanted him, provided he could get onto the floor his senior year.

The second surgery scuttled those plans. Attention largely faded.

But it didn’t from Hofstra. Assistant Mike Farrelly, now the Pride’s acting head coach, first noticed Cramer’s name in the spring of 2018 during the wing’s first rehab process. At the time, it was just that: A name.

Rob Brown, Cramer’s AAU coach with Team Final, suggested to Farrelly he should keep an eye on Cramer, despite the high-major suitors. While those options melted away, Hofstra remained intrigued.

“Hofstra just kept recruiting him,” Brown says. “I said ‘Kvonn, there’s no other school that’s hung in with you like Hofstra.’ They brought him up for a visit and he met the medical staff and the trainers and they gave the thumbs up that they thought he could get back to a form of himself. Kvonn is a loyal kid, and he felt the loyalty that was given to him from Hofstra.”

Still, this was a gamble for Hofstra. It seems almost quaint in the middle of a pandemic to fret about offering scholarships to players a coaching staff hasn’t scouted in person, but it was an understandable concern for the Pride at the time.

Nonetheless, it felt like a risk worth taking.

“We’d kind of built up the relationship at that point, but we were a little bit unsure,” Farrelly says. “It was really taking a leap of faith not to ever watch a kid live and take them. It was really hard to pull the trigger, but he’s a great kid from a great family. He had the physical attributes that we liked. The little bit of film we saw beforehand showed the ability he has and what he could become. And then you’re kind of taking a bet on the kid.”

One other thing clinched it for Cramer: Hofstra offered him the chance to redshirt his first season in Hempstead. The Pride was going to have an older team with a tested backcourt, so minutes would be hard to come by. (Sure enough, all four of Hofstra’s starting perimeter players averaged at least 31.2 minutes for a team that won the CAA tournament).

But it also allowed Cramer the chance to become comfortable on the floor again after the long layoff.

“Hofstra was willing to give me a five-year scholarship,” Cramer says. “When they said that, I was just amazed they still wanted me. It was bigger than basketball. They cared about the person I am.”

Hofstra was eager to see how much progress Cramer would make in an offseason program and the ensuing prototypical second-year jump for a college player. The pandemic wiped out much of that opportunity, and the Pride’s staff didn’t really know what it would get when the team returned to campus.

Meanwhile, Cramer was busy getting into a gym three or four times a week, sometimes settling for an outdoor court in order to cram in work. Brown said many people in the local basketball community made it a point to do their part to help Cramer, whether it was providing a heads up when a facility was available or friends giving him a ride to a practice site while his parents were at work.

“He wanted to make sure he was ready,” Brown says. “He wanted to be ready for coach Farrelly and Hofstra. He didn’t want to go in unprepared and not be there for them the way they were there for him.”

Whatever questions his coaches had over the summer were quickly erased.

“We went from talking about him in late September and early October when we were starting practice and some people on staff said 'I don’t know where he fits or how many minutes he’ll earn,’ ” Farrelly says. “Once we got into live practice, it was clear he makes this team win and that he needs to be on the floor.”

That much is obvious to anyone who has viewed clips of Cramer early this season. Take a second-half play against Fairleigh Dickinson when he received a pass at the 3-point line, took one dribble and took off for a one-handed slam.

For those who saw him before his injuries, it was a feel-good moment, and a reminder of what Cramer could still become at the college level.

“The thing that makes Kvonn a special player is the fact he’s probably 6-6 at best and he’s got these arms where he’s built like a condor,” Brown says. “He probably has a 7-foot-plus wingspan, real long arms, and he was really quick off his feet and athletic. To see that video coming down the middle and dunking, it made you feel like you were in a movie.”

Cramer is a different player today than he was in 2017, but some of those changes would have happened anyway. He says in high school, he was viewed as a dunker—“somebody who can’t shoot, basically a five man.”

His range has improved, as has his defense. And he also has a clear-cut plan for his post-basketball life: Working as a physical therapist.

“Those are the ones that help you get through the injuries in your life, the hard times,” Cramer says. “They’re the ones that really cared for me and wanted me to get back out on the court.”

Now he is, and he’s ready for whatever comes next. Based on the first two weeks of his college career, the highlights have only just begun.

“If he’s not all the way back,” Farrelly says, “Then it’s scary what he was before.”

This week’s podcast

Kevin Ingram and Chris Dortch welcome SEC Network analyst Dane Bradshaw on the newest edition of the Blue Ribbon SEC Podcast.

Click the button below to listen to the podcast.

Thanks for reading!

The next edition of the Blue Ribbon Report is set for release on Dec. 17. If you like what you read, tell your friends about us.

If you want to receive more stories like this one, subscribe to our paid tier for only $7.99 per month (or save $24 per year with an annual subscription).

Also, be sure to pre-order the 40th-anniversary edition of the Blue Ribbon College Basketball Yearbook for the 2020-21 season.